When I was growing up, Frank Zappa was something of a mythical creature. It seemed like he was part guitar god and part political rebel.

I was pretty young when Zappa died but music has always been my world and being a kid of the 90s, there was always a television on in the house. I remember him standing up to Parent’s Music Resource Center and the congressional hearings about censoring albums.

Then, like John Denver, it seemed like Zappa had turned into a living box set. Despite having played his guitar live for the last time in 1991 in Prague, I felt like I commercials for the “Shut Up ‘n’ Play Yer Guitar,” and “You Can’t Do That on Stage Anymore,” CDs were constantly being played.

That was probably how I heard his music the most, from commercials, because his songs (the only one that I really knew was “Don’t Eat The Yellow Snow”) were deemed to inappropriate for my childish ears. Knowing what I know now, he would have hated that.

From then on, Zappa was just an image. Like Che Guevara, if I saw a Zappa mustache logo or The Mothers Of Invention patch on someone’s jacket, it was a symbol that was supposed to mean something – but I don’t think me or the wearer really did get it. Every time I went to the bathroom at my cousin’s college apartment, Frank Zappa was staring back at me.

However, it wasn’t until many years after his death at 52-years-old from prostate cancer in 1993 that I really got a chance to listen to his music. I have a feeling Zappa really would have hated Napster, but it was thanks to YouTube, Spotify and streaming music that I got a chance to listen to a lot of his catalog – which includes 62 albums rebased while he was alive and 53 released posthumously.

Zappa kept all that material and a lot more in his vault. From home movies to unreleased recordings with the likes of Eric Clapton in the Zappa home studio, it’s all in there. And now, many of those recordings are being seen by the public for the first time thanks to a new documentary.

“Zappa,” is the latest film to attempt to understand the genius of the late guitarist and composer. In less than 30 years, Zappa did to the electric guitar what Miles Davis did to the trumpet and Thelonious Monk did to the piano. These composers created pieces of music that would be studied, dissected and taught in universities across the world and which still aren’t completely understood.

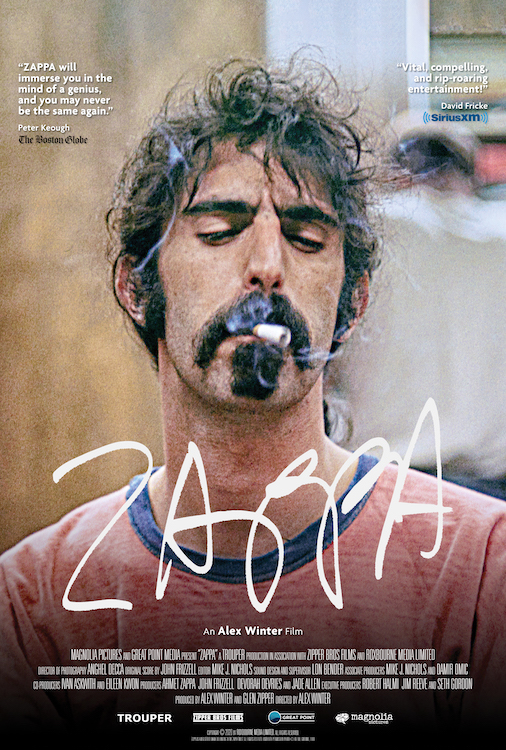

In an attempt to unpack all that music and better understand a man who was complicated and complex, Alex Winter, the Bill of “Bill and Ted’s” fame and producer Glen Zipper were given access to the Zappa vault with the blessing of his wife Gail and created “Zappa,” released Nov. 27 through Magnolia Pictures.

Casual readers of this blog and listeners to the podcast will understand that I am not an expert on anything and that especially includes the subjects of music and movies.

Winter did his best to understand what made Zappa, Zappa. He begins near the end, with his last performance as a musician and saying the Czech Republic’s Velvet Revolution made him want to pick up his guitar for the first time in three years. But what made Zappa want to pick up a guitar to begin with?

Through access to early home movies, Winter takes us into the mind of a boy who was first obsessed with chemistry and then making home movies starring his family. His father worked at a mustard gas factory and moved his family across the country for a better job in better weather.

Then, young Frank Zappa got into music because read an article about French composer Edgard Varèse, whose sounds were described as grotesque. It was from an early age that he began composing, but it wasn’t until later that he started rocking and shocking.

“It always seemed to me that if you could get a laugh out of something, that was good and if you could make life more colorful than it actually was, that was good. So, any artist of individual who worked in those two directions was doing something good.”

-Frank Zappa – “Zappa”

An arrest and six months in jail after the vice squad busted his Studio Z in Cucamonga, California for recording obscene sounds caused him to start the Mothers of Invention in 1965. Zappa realized that if he was going to have his music heard, he was going to have to make it accessible to people. That meant making rock ‘n’ roll music instead of classical.

However, that form of music wouldn’t conform to radio or popular norms. He regularly incorporated classical, jazz, rhythm and blues, gospel and soul into his stage acts and recordings.

From cigarettes being his only drug of choice to being a workaholic to creating lyrics and stage performances that pushed the edges of sexual and language parody, Zappa was a man of paradoxes. Those are spotlighted throughout the film.

As much as he was a businessman, with Barking Pumpkin Records, he was a staunch creative. The battle, presented within the film, is that of an artist struggling to create enough art to fund his creative projects. Those two may have found a balance in the late 60s during his residency at the Garrick Theater in Greenwich Village, New York City.

The archival footage and audio of Zappa is mixed in with interviews with his late wife Gail who died in 2015 as well as musicians who played with him, such as the great guitarist Steve Vai and percussionist Ruth Underwood. It’s these people who were closes to him that helps show the many sides and moods of Zappa.

Absent from the film is his son, Dweezil, except for some archival footage of he and Moon as well as the other Zappa children, Diva and Ahmet. The latter, who runs the Zappa Family Trust, is the producer of the film.

The movie does, however, show the creative projects that Zappa undertook, including the making of the claymation film “Baby Snakes,” which was one of his few creative outlets while recuperating from a near-tragic injury after a fan pushed him off stage in London.

By the end of just more than two hours of riveting storytelling, the only thing that seems consistent in the film is the drive of Zappa to create the music that he heard in his head.

In the beginning, the difficulty was finding the best most reliable musicians to create music that was popular enough to be paid. By the end it was how to create the most important projects before time runs out.

For fans of Frank Zappa, this latest documentary is a must-watch to help fill in some of the pieces, like what happened behind-the-scenes during his last interview. For those unfamiliar with all three acts of “Joe’s Garage”, it’s a humanizing portrait of a man who worked his hardest to express himself as a 20th-century American composer.

Get “Zappa” from where you stream movies at home. Details via the “Zappa” movie website.